It is the great misfortune of the West that its way of life is almost universally envied without being universally available or completely understood. The phenomenon has long been painfully evident in Africa, but it has never been more obvious or incongruous than in the Gulf today.

Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in August and the arrival of 200,000 US troops and hundreds of journalists in Saudi Arabia have exposed to public view the difficulties faced by conservative and publicly religious regimes whose citizens are tempted by everything from sex to alcohol to Western music and visions of democracy.

‘Hypocrisy’ is not a big enough word to describe the cultural confusion wrought by three decades of oil money and economic development in the traditional sheikhdoms of the Arabian peninsula. Saudi Arabia is a country where alcohol is banned and where the religious police have been known to enter shops and smash glasses which look as if they could be used for wine. It is also a country where the rich drink magnums of black-market French brandy in the safety of their homes, the poor cross the causeway to get drunk on the island of Bahrain, and foreigners in their isolated compounds sip computer-cleaning fluid or the home-made sugar alcohol called Siddiqi (‘my friend’, or Sid for short). Women are forbidden to drive cars, are hardly allowed to work, and are clothed and veiled in black when they leave the house; adulterers are sometimes stoned to death in public. There are no cinemas and the nearest thing to pornography is the sight of Russian synchronised swimmers in the pool at the Intercontinental Hotel in neighbouring Abu Dhabi. But many of the men think nothing of paying for sex in London or Bangkok.

Saudi soldiers guarding the US Embassy in Riyadh listen to the sound of disco music from the Wednesday night parties and ask with a mixture of horror and envy if it is true that people are dancing and drinking whisky by the pool. A trainee Saudi aircraft engineer in Dhahran, hitchhiking into town from the Airport, says he wants to go to London because he has heard that you can just go up to any woman in the street – not only a prostitute – and ask her to have sex with you: he finds it difficult to grasp the idea that it would be wiser to get to know her first.

Mutual cultural incomprehension is the Gulf’s stock-in-trade, as visible in the contempt felt by foreign guest workers for their hosts as in the Neoclassical concrete façades of Saudi palaces in Jeddah and the ‘English week’ at a Dubai hotel, where I once saw a miserable Thai indentured labourer employed as a waitress and dressed as someone’s idea of a country milkmaid in bonnet and frock. The Iraqi invasion, which has brought gun-toting American women troops to the streets of Saudi Arabia, has redoubled the confusion. Like some Kuwaiti women refugees, America’s female soldiers drive vehicles on the roads. They also sweat through their T-shirts in public places and eat bacon at the airbases for breakfast. As the muezzin call the faithful to prayer in Dhahran, soldiers in one of the base’s hangars glance up at a banner full of messages of support sent by the students of Manchester township, New Jersey, USA. ‘Kick Some Butt!’ one of the children has scrawled. Meanwhile, in Washington and the capitals of Europe, politicians are asking themselves if they really want to go to war for reactionary and undemocratic Gulf governments as well as for oil.

The Gulf’s ruling families are resisting change, but there is a group of people in the region who bridge the cultural gap between the West and Islam, and who believe that they can use the shock of the Gulf crisis to liberalise their societies and work towards necessary cultural and political compromises. They are trying to answer the question: is the Gulf increasingly pursuing Western values, with a hypocritical overlay of Islam and Arabism, or is it essentially Islamic with a veneer of Westernism? These people, businessmen and intellectuals, are usually educated in the US or Britain and speak fluent English or American as well as Arabic. One of the younger members of this loose alliance of like-minded Gulf Arabs was once described to me as a ‘Bahraini yuppie’. Another, a Saudi official, told me how much he hated traditional Arab declamatory poetry as tribal leader after tribal leader heaped extravagant praise on Prince Sultan, the Saudi Defence Minister, and his late father Adbul-Aziz, at a recent ceremony near the Yemeni border, where Sultan was on a tour to inspect the troops. The invasion has galvanised the Gulf’s emergent liberals, and many are now attempting to redress long-standing grievances.

Among their primary aims is more freedom of information. Ahmed – not his real name – explains over a fine bottle of French wine in a Dubai restaurant the frustrations of intellectual life in the Gulf. Literature is censored; the works of Marx and Lenin, even after the downfall of Communism in Europe, must be smuggled in. Newspapers and television stations are abysmal, and local issues are almost never analysed in depth. ‘One day Saddam is a friend, the next he is Satan on earth,’ he says. ‘Why had our rulers hidden these things?’ The results of population censuses are usually kept secret, because governments are embarrassed by the small number of native inhabitants and their overwhelming dependence on foreign workers. There was a census covering Dubai which would have helped businessmen like Ahmed four years ago. ‘What were the results?’ he asks. ‘I’d love to know. It’s important.’ Near his home, thieves robbed a house and killed a maid, and a week later half a dozen people – presumably illegal Iranian immigrants – were pursued by helicopter after they jumped off a boat: but no information was forthcoming. ‘We don’t know what’s going on in our own country,’ he says.

It is the same in Saudi Arabia. Rumours run wild for want of even the most basic facts. I was once told the unlikely tale that it was impossible to drive from Riyadh to Jeddah because of bandits, following a series of highway robberies by a renegade Bedouin leader with guns and Toyota Landcruisers. Government acknowledgment of the problem came only with the announcement that the suspects had been executed. Every day Saudis with PhDs are bombarded not with useful news but with junk about how the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques (King Fahd) has received a message from the President of Djibouti. Realism is at a premium, and three months after the arrival of US troops King Fahd still talks about ‘Arab and friendly forces’ as if most of the soldiers were Arabs. On Reuter Monitor screens in Saudi hotels you can usually call up detailed news about Africa in French, about Asia in English, or about Europe in German, but nothing about the Middle East in any language. It is too close to home.

The censorship is social as well as political. There must be profound cultural insecurity in a regime which outlaws non-Moslem worship, routinely cuts the word ‘ham’ out of the Blondie cartoon strips which appear in local newspapers, and employs men with black felt-tip pens to cross out whisky advertisements in foreign publications. The most bizarre example of newspaper censorship I saw on my latest trip was the blacking-out of a cartoon mermaid in a still photograph from a Walt Disney film. Saudis themselves are quick to point out that most of the censorship, on the political side at least, is neither particularly Islamic nor particularly effective. Articles torn out of foreign magazines and newspapers gain the lurid attraction of the illegal and are simply received by fax.

Despite the best efforts of the Saudi Ministry of Information – known to some as the Ministry of Praise of Denials – the arguments and the agonising about Saudi Arabia’s cultural confusion are becoming increasingly difficult to hide. Wahib bin Zagr, a leading businessman and Chairman of the Saudi-Cairo Bank, wrote in the English-language Arab News in October about the dangers of a Saudi ‘split personality’. He emphasised the extraordinary contrast between Saudis, who absorb Western culture when they visit the West, and Westerners, who are isolated from Saudi culture when they come to earn money in Saudi Arabia. ‘We even compete among ourselves in boasts of how much we understand their culture and their faith,’ he wrote. ‘At the same time we don’t care if they are completely ignorant of our values and we make very few attempts to help them understand our faith.’

Such thoughts are hardly subversive, but credit is due to Khaled al-Maeena, the editor of the Arab News, for his efforts since the Gulf crisis to begin to address some of the important issues in Saudi society long ignored by the media. In particular, the Arab News (whose correspondent Faiza Ambah is said to be the only Saudi woman journalist working in the Kingdom) has run a series of ground-breaking articles about the role of women. For one of the articles, Ambah asked Saudi women about their ambitions. ‘When asked what changes they would like the crisis to bring about,’ she wrote, ‘a torrent of demands spill out. “Work opportunities, so we can manage on our own if there’s war,” says one. “Driving,” says another, “so we can defend ourselves in case of emergency.” “Better coverage of local events, so we don’t have to listen to rumours,” they add.’

The public airing of liberal ideas does not extend to discussion about the Saudi system of government or talk of democratisation, although the promise by Kuwait’s exiled ruling family, made at a conference in Jeddah, to restore a measure of democracy in a liberated Kuwait has allowed newspapers to mention the issue by the back door. In private, the matter is hotly debated, and groups of businessmen have confronted their princes to ask for greater representation. There was one such meeting in Riyadh involving Prince Salman, the city’s governor and brother of King Fahd, and another more heated discussion in Bahrain with Sheikh Khalifa, the Prime Minister. The ruling families, with the exception of a few relatively liberal princes, argue that the traditional system of government is not only benign but infinitely preferable to the tyranny of Iraq or Syria. The reformers say that the institution of the majlis – the regular meetings where subjects demand favours of their rulers – is wholly inadequate as a means of shaping national policy in a modern nation state. ‘It’s absolute nonsense,’ retorts one Saudi businessman when asked if the King’s majlis is not an alternative form of democracy. ‘These days there are too many people to attend in person. A couple of old ulema whisper in his ear. Then they all have dinner and a couple of planted people ask questions.’

The old balance of power between the ruler and the ruled has been distorted by the oil revenues accruing to the state, whose finances are indistinguishable from those of the ruling family. Kings, princes and sheikhs no longer depend at all on the financial support of the merchants, or as much as they used to on the military assistance of the tribesmen, and therefore no longer feel obliged to listen to what they say. At the same time, the ranks of royal families become more swollen every year. There are thousands of princelings in Qatar demanding sinecures and subsidies and building rows of palaces along the main road into the desert. In Saudi Arabia the British Embassy keeps a list of some two thousand bona fide princes who are entitled to special treatment when they submit their visa applications at the last minute; the rest are not influential enough to bypass the normal regulations.

The Gulf’s intelligentsia often hope for some kind of constitutional monarchy, but they expect reforms to take a long time. Above all, they recognise that they are a sophisticated minority, albeit a growing one, and that most of the region’s inhabitants could not care less as long as their rulers are sufficiently generous in distributing oil money to the people. If Saudi Arabia was democratic, one businessman says, the National Assembly would be 70 per cent Bedouin and the country might become less rather than more liberal.

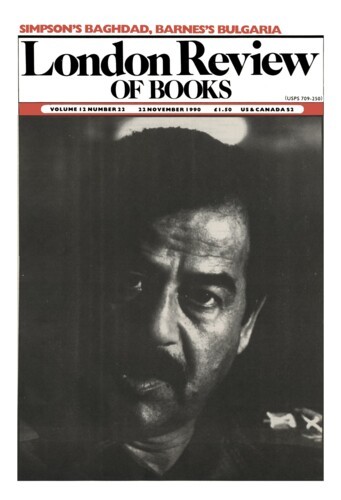

Several books are already being written about the Gulf crisis. They are likely to focus on the career of Saddam Hussein and the blunders of the Western countries which armed him, but they may have difficulty analysing the long-term effects of the invasion of Kuwait on 2 August on the Arab Gulf states. The ruling families seem no more inclined than before to open the door to real democratisation, whatever the pressures from their domestic critics and their foreign allies, but the presence of American troops in Saudi Arabia and the jolt given to the whole region by Saddam’s aggression have exposed more than ever before the contradictions between reality and official policy. Saudis as well as foreigners pace around fretfully outside the stores in the Kingdom’s gleaming, American-style shopping-malls when they close for Moslem prayers in accordance with the country’s puritanical regulations. Democracy and freedom of information go hand in hand, and the Government’s attempts to censor the outside world – the Western world – in an age of fax machines, satellite television and mass air travel look increasingly futile.

‘Within twenty years or less people have moved from desert tents with bushes as lavatories to villas with gold-plated bath taps. The ideological confusion which arises from this contradiction is enormous,’ wrote Helen Lackner in her book A House built on Sand, a political economy of Saudi Arabia. She also observed:

One reason why the regime is so opposed to external intellectual influences is that the continued equilibrium between the reality of materialism caused by rapid Westernisation and the fiction of Wahhabism which has lost its real roots with the destruction of the age-old desert culture can only be maintained by an intellectual petrification ...

Such a situation cannot last and the immediate prospects for Saudi Arabia are bleak. The ruling family are bound to support the shell of Wahhabism as it is necessary for their control of the state, while pursuing further ‘modernisation’ policies which may give the people some material improvement but lock them in a contradiction between the ideology they are brought up with and the extravagant materialist daily life they are expected to aspire to. The forced intellectual sterility can only temporarily prevent the emergence of a new culture.

Lackner’s book was published 12 years ago in the reign of King Khaled, but its conclusions are just as valid today, with Fahd on the throne and the Iraqi Army on the border.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.