In the introduction he wrote to the Magnus memoir of the Foreign Legion, D.H. Lawrence remarked that he hated ‘terrible’ things, ‘and the people to whom they happen.’ A reason for keeping away from Jean Rhys, but in any case they would hardly have appealed to each other. When she was young she liked adventurers, and married one, but later in her long life she preferred gentle and gentlemanly types who wanted to cherish her, though they seldom or never succeeded. As Carole Angier acutely observes, she gravitated towards men with ‘social confidence and inner uncertainty’. Adultery and promiscuity were, oddly enough, not her problems: she craved, or thought she did, ‘the twins freedom and safety’ (dissimilar twins, one might have thought) and the respectability of a married name. Her later spouses clung to her with suicidal fidelity at the cost of their finances, their health and sanity. They died worn out, but she kept going, on gin, whisky and Algerian wine, to die at a great age, famous at last, completing an early book called Smile Please.

It is probably hard for the young to imagine the one-time lure of what was known as Bohemia, refuge from a socially repressive and aggressively snobbish age. Ella Gwendoline Rees Williams, as she began, was born in Dominica in a plantation family which had seen better days but with good connections, returning to England for public school and careers in banking or the Army. Jean’s brothers frequently, if disapprovingly, bailed her out in later life. Dominica was a sinister if beautiful place, hostile and tyrannical to a child, and so in a different way was the prestigious Perse school at Cambridge, which took women’s education seriously. After that it was a relief to go on the town in some degree, settling into night-clubs and taking up with rackety gentlemen who nonetheless behaved and dressed well, seeming to offer a degree of stability along with freedom. In her story ‘Goodbye Marcus, goodbye Rose’ a girl called Phoebe recites:

If no one ever marries me

And I don’t see why they should.

For nurse says I’m not pretty

And I’m seldom very good ...

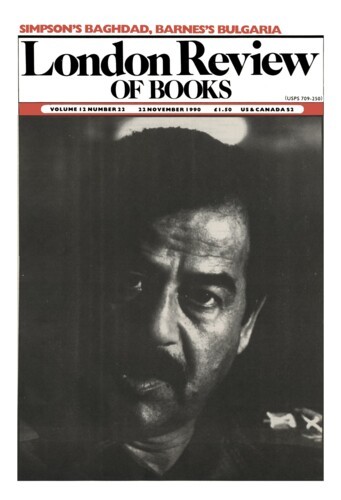

She was pretty, if the photo on the cover is anything to go by, but it gave her no confidence. Finally she took up with a young Dutchman, John Lenglet, who came from a background as respectable as her own, though he was already married, to an actress, and was still not divorced when he and Jean celebrated their bigamous wedding in The Hague in 1919. Sasha in Good Morning, Midnight doesn’t like The Hague very much, and they soon went to Vienna, where Jean bore a son who died after a few weeks, and later a daughter, Maryvonne, who was to become, with her father, a heroine of the Dutch resistance in the second war, and who after an eventful life of her own still kept up with her mother in Jean’s old age. John Lenglet was condemned to death in the war, survived Sachsenshausen concentration camp and lived to remarry a penniless Polish countess and write books about it all.

But that was years later. In Vienna in 1920 John played the currency market and became briefly rich, but things went wrong and they had to leave hurriedly for Paris, where he was eventually arrested and imprisoned. Meanwhile Jean took up with Ford Madox Ford, who encouraged and supervised her urge to become a writer. Stella Benson, Ford’s current lady, tried and failed to put her foot down but put a finger on the source of Jean’s power and appeal, in her writing as in her life: ‘Here was I cast for the role of the fortunate wife who held all the cards, and she for that of the poor, brave and desperate beggar who was doomed to be let down by the bourgeoisie. I learnt what a powerful weapon lies in weakness and pathos, and how strong is the position of the person who has nothing to lose, and I simply hated my role.’ One, perhaps the main, secret of Jean’s novels is the comfort the reader derives from the passive hopelessness of the heroine’s situation. Carole Angier calls Jean Rhys and Ford Madox Ford ‘perhaps the two greatest artists in self-pity in English fiction’. Ford has the edge technically, particularly through his use of the unreliable narrator: for no one, in her own way, could be more reliable than a Jean Rhys heroine. The reader is never left in any doubt that things are just as bad as she finds them to be.

Yet perhaps self-pity is not quite the right word for it. There is something more primeval about the Rhys heroine’s terminal state of uncaringness. She has become like a reptile in the steaming forests of Dominica, crouched unblinking in the semi-darkness. Her comfort is having no feeling, not even the flicker of trench humour needed to feel the equivalent of King Lear’s ‘The worst is not so long as we can say “This is the worst.” ’ Things have got beyond the refuge of speech – and besides, she is entirely alone. The almost placid end of Good Morning, Midnight, when the hated commercial traveller in his dressing-gown appears at the door of Sasha’s horrible hotel room, is certainly memorable. The strange comfort of it may be the drug the Rhys addict goes for, for the commis voyageur is everything to be fled from which becomes our fate in the end.

Good Morning, Midnight finally appeared on the eve of the Second World War, and vanished without trace. No one at that time was interested in such a gloomy book, and its moment did not come until the revival of the appetite for lowering fiction in the Fifties and Sixties. By the time the novel came out, Jean had become Mrs Tilden Smith, and her kind supportive new husband, an impoverished publisher’s reader, helped her with it considerably. The war made her drink even more, although in the alcoholic drought of those days, and having no money anyway, it is a puzzle where she got it from – a puzzle her biographer does not solve. She only remarks rather owlishly that Jean hated the war and that it is ‘terrible’ to think of her raging at England, having water thrown over her once when she was drunk and disorderly – ‘and this was the woman who had already written some of the finest prose of our century.’ To be fair, Angier also analyses the appeal of that prose very well: how the obsessively repetitive heroines – all Jean, of course – endear themselves to her readers’ secret sense of their own awfulness, an awfulness preferable to the niceness of nice people. And yet ‘she didn’t want to be loved and pitied for being awful and brave, as she was: or to be admired for being a great writer, as she was. She wanted to be loved and admired for being what she wasn’t: ordinary, gentle, entirely beautiful. It was an impossible desire.’

Meanwhile the war for which she had no time went on, and her husband Leslie was in the RAF, and she tormented poor Mr Feast, the well-meaning parson of the village near the air station in whose rectory she had digs, and told him that Leslie drank, which was not true. After the war Leslie died worn out of heart trouble, and she married a relative of his. Max Hamer, another gentle upright man with – presumably – a secret passion for Bohemia. Max, who had been a Naval officer most of his life, did not remain upright for long, becoming involved with crooked solicitor friends and spending two years in Maidstone gaol, a town which Carole Angier pardonably confuses with Maidenhead. Before that had taken place the saga of Beckenham, where their attempt to set up as good surburban householders had come to a predictable end.

Meanwhile Jean had vanished altogether from the literary scene. Even Francis Wyndham, who had become a great admirer, thought he was rediscovering a dead author. Even the publisher thought so. ‘I don’t know why Constable thought I was dead,’ Jean said, when the BBC eventually ran her to earth in 1956. ‘It does seem more fitting I know, but life is never neat and tidy.’ She was revived. Good Morning, Midnight and her other books were sought out and praised. She started to write Wide Sargasso Sea, about the first wife of Jane Eyre’s Mr Rochester, and that, too, was a great success when it came out in 1968, although it is somehow appropriate that things continued to go wrong, and that she hated the picturesque Devon cottage found for her after the end of Max, where she drank as much as ever. Still, when she died there in 1979 she had become a grand old lady of the English novel.

Barbara Pym died a year later at her cottage in Oxfordshire, having thoroughly enjoyed her retirement from a London office, and having also been rediscovered and made famous after years of being rejected by the swinging publishers of the Sixties – the same kind, no doubt, who had suddenly seen the possibilities of Jean Rhys. The heroines of both authors have their own way of coping with the unsatisfactoriness of things: Jean Rhys’s by going to bed with a bottle; Barbara Pym’s by going out to a jumble sale, or to an Anglican service on ‘one of those Sundays after Trinity’. Pym is in the end the tougher of the two (one of her male characters ‘marvels at the sharpness of even the nicest women’), and she is unquestionably the more sophisticated narrator, just as Jane Austen has a cooler head for fiction than Charlotte Brontë. One can read a Pym again and again, like playing patience or stitching grospoint, but I doubt if even her warmest admirers would want to revisit the Rhys haunts more than once or twice. In the end, Bohemia becomes so boring.

In addition to an almost indecent interest in other people Pym developed the Austen knack of casting herself with complete conviction in different fictional roles: the beady-eyed romantic spinster; the childless placidly bitchy wife with few outlets for her curiosity; the office worker who lives for her successive love affairs; the young girl at the starting-post; the widow in the terminal bed-sit. The third role, that of Prudence in Jane and Prudence, was, she said, her own favourite, and it was one she tried out early as an Oxford student, falling for a number of handsome young men with whom passion was less important than romance, followed by a circle of friendship which remained unbroken all her life. Would she have married the most ardent of these crushes – Henry Harvey, later of the British Council – if he had asked her? The answer seems to have been yes, in which case we might well have had no novels, as we should probably have had none if Jane Austen had taken the plunge. But at 19 she was already a dedicated note-taker, with ambitions to become a novelist, and Harvey, the youthful Prince Hal of his own little circle, valued her as a fast girl and good sport with whom a perpetual jokeyness was the thing, as well as a degree of physical intimacy.

How far this extended it is not easy to say, although Barbara’s diary records being found by his closest friend reading Samson Agonistes in bed with Henry ‘with nothing on’. ‘Really rather funny. I stayed to supper. Jockie’ – the friend – ‘forgave me as I was penitent and was very sweet.’ There is an innocence about this which Iago ingeniously suggests about Desdemona – ‘to be naked with her friend in bed/An hour or so, not meaning any harm’ – and such goings-on were probably not infrequent in the supervised but girl-hungry university of the Twenties and Thirties. The real Iago, so to speak, was no doubt a very chummy sort of person. In a reminiscent talk to the PEN Club Harvey explained that ‘friendship was stronger than romance for all of us in those early days,’ and that Barbara’s own feelings ‘stayed in her head and her heart.’ The free and easy girl who in fact didn’t, when it came to the point, was a phenomenon of those days (Barbara was up from 1931 to 34), and in the novel Prudence teases Jane’s curiosity about what actually goes on between her and her lovers. One of her fiction’s distinctive pleasures is its unique mixture of innocence and shamelessness; Pym gives back an edge to the kind of gossipy curiosity which languished in the permissive atmosphere of the Sixties novel. She attracted ‘nice’ men too, and had several proposals.

Her great love, Henry Harvey, featured in her own and other novels, including one by Robert Liddell (‘Jockie’), who was a colleague in the British Council. Although she necessarily draws a good deal on the source of these matters, the collection of Pym letters and diaries, A Very Private Eye, which she coedited with Barbara’s sister, Hazel Holt has now done a highly competent and admirable job as biographer. A colleague at the International African Institute in London, where Barbara worked, she understands well the ins and outs of the ramifying Pym background, and her book is a valuable record of an almost vanished setting and social culture, as well as a must for Pym-lovers, and always sympathetic to the priorities of that world (‘Barbara enjoyed her stay in Rome but ... would see the Eternal City primarily as a setting for a parish holiday for the vicar and congregation of a North London church.’)

She had a conventional and happy childhood and upbringing – father a solicitor in Oswestry, school at Liverpool College, Huyton – but like most conventional backgrounds it had its unexpected side. Though it was never mentioned to his two daughters, their father was illegitimate, the son of a West Country servant and a wild young Somersetshire squire. After Barbara’s death her sister made the discovery when tracing family papers, and remarked how fascinated Barbara would have been by it, for her sleuthing instincts – an aspect of her romanticism – were highly developed. Probably they frightened men a bit, though they may have been flattering too. She fell madly in love with Gordon Glover, a BBC man and one time protégé of Robert Graves, when she was staying with his supportive divorced wife in Bristol during the war. When he dropped the affair she joined the Wrens, fell mildly for a handsome but rather ‘common’ paymaster-lieutenant in Naples, and decided when demobbed to live with her sister, who had separated from a wartime husband. While she worked in London the novels began to come, beginning in 1950 with Some Tame Gazelle, of which an unpublished version had been written before the war. Excellent Women, her most popular, followed: the Pym world had arrived.

Like all such worlds – Jane Austen’s no exception – it was first inspired by other books, and rather surprising ones: the metaphysical poets, Aldous Huxley’s first and best novel Crome Yellow, Ivy Compton-Burnett, Private Lives. The Church is reliable but not essential. Life is just as grim as in Jean Rhys but funnier: what matters are the comforts and compensations. Men are a dependable source of comedy – the more so for an invisible reason, that they found her books ‘so sad’ – and are given to sentiment and self-dramatisation. Besides, they want one thing only, although Miss Doggett of Jane and Prudence, who was long ago told this, cannot actually now remember what it is.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.