Accompanied by a growing pile of political books, I spent most of September and half of October travelling from pillar to post and from party conference to party conference – from Blackpool to Torquay to Dundee to Bournemouth and back to where we began in Blackpool. For years now I have set out on this dismal pilgrimage filled with hope and health and holiday sun, only to return filled with alcohol, tobacco fumes and hot air. The conference season is an annual ritual, a ceremonial enactment of the entire political liturgy, including the beatification of leaders and the veneration of relics, all of it carried out in front of the altar of the television cameras.

The importance which the conferences have assumed in the political calendar over the last twenty years has a lot to do with the fact that they are there to be televised while the House of Commons is not. So, because there is something to point the cameras at – ‘if it moves, film it’ is the principle of political journalism in the television age – the viewers are offered hushed commentaries about the liturgical meaning of the reference back or the remission of composites.

Out of the conferences come images, distilled from the continuous flood of daytime transmissions for encapsulisation in the main nightly news bulletins – priceless moments of political prime time which show Kinnock up or Thatcher down or Owen playing prime minister for a day. And built around those images come ideas and patterns to be repeated through the political year, whether true or false – a seasonal yield of misty perceptions which are all we know of political reality.

The philosopher Charles Taylor has remarked that politics is ‘what’s going on’, or something to that effect. But how the hell are we to know what’s going on, I thought while on my way to the Trades Union Congress? What is going on is in some part what we say is going on: but if we don’t know what is going on, then what is going on? I’d often written that appearance in politics is the greater part of reality and been taken to be making a point about media manipulation. What I had meant was that the muddle of events could have no meaning without some principle of interpretation, and that what we choose to think is going on, the appearance of events, becomes the wrapping for what is imagined to be reality. The invisible man needs clothes.

The conference season would need a theme, a shape, a meaning – how else could one write about it interestingly? This year it soon acquired one. ‘Three-party politics are here to stay’ became every commentator’s punchline. Here, yes: but to stay? And yet if we all said so, and went on saying so, and more and more people came to think so, and behaved accordingly, then what was quite possibly only the appearance of things would have become the reality. Only, of course, if we were sufficiently correct in the first place, for myths are not spun from nothing. But what if we were right to think that we felt the tremor of the ground beneath our feet, a rumbling earthquake that would slowly change the political landscape? Gramsci once felt the same: ‘The old is dying and the new cannot be born – and in the state of interregnum there arise many morbid symptoms.’ Gramsci was referring to the death of capitalism, while we are talking about the death of socialism.

The TUC did its best to confirm the diagnosis. To the huge embarrassment of Neil Kinnock, it supported the policy which later, by the same union block votes, passed at the Labour Party Conference and pledged the reimbursement of the National Union of Mineworkers for the fines and sequestrations incurred by its illegal behaviour during the strike. Kinnock, who was arriving in Blackpool that very day, at once repudiated the decision and made it plain that no Labour government would act retrospectively to uphold law-breaking. This was the prelude to the famous speech which he made in Bournemouth a month later. On the same day, however, a more ominous development occurred. By reaffirming its prohibition against unions accepting government money to finance the ballots now prescribed by the law (democracy is exceedingly expensive), the Congress put itself on a collision course with the engineers (AUEW) and the electricians (EEPTU), who are determined to take the money. If this leads to their expulsion from the Congress, a rival trade-union centre could form around these unions and around the breakaway Union of Democratic Mineworkers which, a few weeks later, was heavily endorsed by the Nottinghamshire miners, and narrowly in the smaller South Derbyshire coalfield.

These developments have potentially profound political implications. First, they draw attention to the tricky subject of the trade unions’ position under the law. If the AUEW and EEPTU are expelled, it will be for refusing to defy the law of the land. Secondly, they leave the unions looking ambivalent about democracy. There are genuine difficulties here. How is the TUC to adopt collective positions when they are subject to referenda within affiliated unions? Whose democratic decision prevails – the state’s or the federation’s? The dilemma is still more acute with the UDM, for if one group of members within a union are permitted to break away by their own democratic decision none of the great conglomerate unions will be safe. But by refusing to recognise the breakaway the TUC will appear to the public to be siding with Arthur Scargill.

A third consequence, flowing from these two, is that the TUC – especially were it to split into rival political centres – will look an unconvincing partner for a Labour government whose expansionary economic policies are premised on a special degree of trade-union co-operation. Moreover, the decisions of the Labour Party itself would be reached by the block votes of the unions remaining affiliated to the TUC. Not only would that tilt the Conference to the left, at a time when Kinnock is trying to repossess the centre ground, but it would call into question the whole constitutional structure of the Labour movement.

In part, these developments can be attributed to stupidity, incompetence, ill-will and other contingencies which aggravate the state of immobilism which has long afflicted the British trade union movement. To depart from the carthorse image for once, the TUC is like a heavy artillery piece in a muddy Flanders field: point it in one direction and it is a major undertaking to point it in another. But was there more to what was ‘going on’ in Blackpool? In the preceding few days the commentators had begun to discover the ‘dual labour market’ or the ‘Germanisation’ of the English working classes. The core of the work-force would be highly-paid, home-owning members of BUPA, and covered by what, in the new trade-union parlance, are called ‘total agreements’, which customarily include no-strike clauses; beneath the core would be a sub-class consisting of the unemployed and unskilled, of part-time workers and women, blacks and foreigners. Here, it was said, was the real nature of the split emerging in the TUC. Some support for this theory was provided by an officer of the EEPTU who told the Congress, which closed its ears and hissed and booed, that the unions which negotiated these total agreements were the only kind of unions you could get people to join these days, and that in factories up and down the country the language of class war doesn’t even earn you a yawn. Farewell to the working class?

By the time of the Labour Party Conference I’d had time to read the 1983 Election study, How Britain votes which explodes the notion that class-voting is on the wane. This is a good example of my appearance-reality theorem. The idea that home ownership, consumerism, holidays abroad, were undermining class solidarity had in recent years become central to our picture of a changing political society and, in particular, to the notion that the Labour Party was in secular decline. And now here were these young revisionist psephologists upsetting the whole neat theory and telling us that there was little if any statistical evidence to show that class was any less important as a source of voting behaviour.

What has happened, they say, is not a withering away of class but a change in the structure of the classes. They arrive at this conclusion by rearranging the classes according to economic interests in place of the advertising and market-research classifications of A, B, C1, C2 etc. They doubt whether income and life-styles are very useful determinants of political behaviour, and they prefer the competitive position of different groups in the labour market. In this way, the high-earning affluent manual worker remains working class while the own-account manual worker, who may earn a good deal less, is placed within the petty bourgeoisie. The working class, so redefined, is found to have declined from 47 per cent of the electorate in 1964 to 34 per cent in 1983. The big growth was in the routine non-manual or white-collar labour force (from 18 to 24 per cent), and in the salariat of managers and executives, professionals and semi-professionals (from 18 to 27 per cent). Since 1964, they conclude, ‘Britain has been transformed from a blue-collar society into a white-collar one.’

Those of us who had supposed class-voting to be in decline were mistaking the decline of Labour for the decline of class. ‘Labour remained a class party in 1983; it was simply a less successful class party than before.’ This leads them to search for ‘political sources’ for the successes and failures of the parties, in place of explanations which rely on the changing character of the classes. About half of Labour’s electoral decline since 1964 can be attributed to the diminution of the working class. What other explanations can be found? Housing tenure turns out not to be much help. (The authors find no evidence that people who had bought their council houses were more likely than others to defect from Labour to Conservative in 1983.) The theory that post-industrial, or post-materialist, values are taking over from bread-and-butter issues doesn’t stand up. Nor does the consumer theory of voting. If people had voted strictly according to where they stood on the issues in 1983, the result of the election would have been Conservatives 35 per cent, Labour 35 per cent, Alliance 31 per cent.

How do people vote then? According to a general fit between the characteristics of a party and their own ideological predilections. We used to talk about this as ‘image’. At the beginning of the Sixties Labour was thought to have too much of a ‘cloth cap image’. Today it is harmed by its image as the party of nationalisation and intervention at a time when there has been an ideological shift towards free enterprise and privatisation. But we should not, the authors warn us, take ideological change to be merely the consequence of social change. Moreover, social trends are not inexorable. Within the confines of class voting there is room enough for politics.

How Britain votes reinstates the future of the Labour Party, and indeed of the other parties, as a political question which is not predetermined by social demographics. Ideological change, or changes in what we call the ‘climate of opinion’, is also an important factor and the outcome of the game will be decided, at least in part, by the political skill of the players. At Bournemouth Neil Kinnock showed that principled leadership and a bit of panache can pay off even in the most unpromising circumstances. Nevertheless, he is up against a Labour Movement which is stuck with a declining class base, and increasingly, too, with a regionalised base: how is it to extend its appeal beyond those frontiers while continuing to appease the activists entrenched within, and to serve at the same time the sectional interests of the trade unions?

If a political explanation of Labour’s decline is required, it is that it has been unable to adapt sufficiently to the changing sociological circumstances and ideological preferences of the electorate. Indeed, in so far as it has adapted, it has done so mostly in wrong directions. This condition seems to me to be a systemic one, which will continue to make it difficult, if not well nigh impossible, for Kinnock to extend his party’s appeal far enough beyond its diminishing class stronghold.

The future of the SDP-Liberal Alliance, I have long considered, is chiefly a function of the future of the Labour Party as an electoral force. Nevertheless, it is useful to be reminded by Roy Jenkins in the preface to a collection of his essays and speeches that he broke with Labour ‘not because I feared it could not be elected, but because, with its new policies, I did not want it to be elected’. In the 1979 Dimbleby Lecture, here reprinted, he posited a new constituency which he characterised as the ‘radical centre’, although, as he explains, he envisaged the SDP as ‘a radical alternative to the Tories, a left-of-centre party if the old hemicycle terms are to be used’.

The election study finds that since Jenkins’s seminal lecture the Alliance ‘has created (or at least acquired) a new ideological base or heartland that the Liberals alone did not have in the past’. This body of opinion dissents from Labour on the ‘class issues’ – nationalisation and so on, but also, to some extent, redistribution – and from the Conservatives on the ‘liberal issues’ – health, education, civil liberties. The ideological profile of Alliance voters fits well the description ‘radical centre’.

The Alliance has developed something of a class base of its own within the salariat, especially among its more highly educated members; the base is smaller and less secure than the other parties’, and its ideological appeal less distinctive, but, nevertheless, the Alliance is no longer to be dismissed, as in the conventional wisdom, as a party of protest without other visible means of support. And the same is true even of the Liberals. In 1974 Liberal voters were all over the place, confirming their party’s reputation as an incoherent and essentially apolitical party of protest: in 1979 they put on a more coherent show, and in 1983, now together with the SDP, made electoral gains within their own ideological heartland.

The Alliance parties played up nicely to these new images at their two conferences. At the SDP’s the ‘salariat’ was well in evidence, there was a lot of talk about ‘talking the language of the new politics’, and I think I heard Shirley Williams refer to the ‘nodes of the new society’. Ian Bradley sees this new society as a post-social democratic society. For him, liberalism is a mystical cult of the individual. Everything that suits his argument, or rather quasi-religious faith, is dragged into service, including the growth of the self-employed, although the election study shows that 71 per cent of them voted Conservative. But there was very little of his sort of cranky nonsense at this year’s Liberal Assembly in Dundee, and for once the Liberal Party looked the part of a conventional power-seeking party.

The two conferences succeeded in creating at least the appearance of an Alliance advance. Penalised by the electoral system and marginalised by Parliamentary procedure, only during the conference season and election campaigns do the Alliance parties benefit from disproportionate representation in the media. For what turned out to be a brief moment of glory they led the field in two of the major opinion polls. The fashionable talk was of hung Parliaments and coalitions and of what the Queen might or might not do. The appearance began to take on an air of reality.

Labour later shot ahead in the polls as a result of Kinnock’s stand against the Militants and Arthur Scargill. By the time the Conservatives met in Blackpool, where we had begun with the TUC, it was plain that in the state of interregnum between the old and the new an extreme volatility on the part of the voters was one of the morbid symptoms. But if read carefully the polls also suggested that the Government had embarked on a modest recovery from the pits of midsummer. Two of the polls taken in October, after the completion of the conferences, put the Tories back in the lead; averaged out, they show Labour and Conservative running virtually neck-and-neck at around the 35 per cent mark, with the Alliance slumped back to 28 per cent.

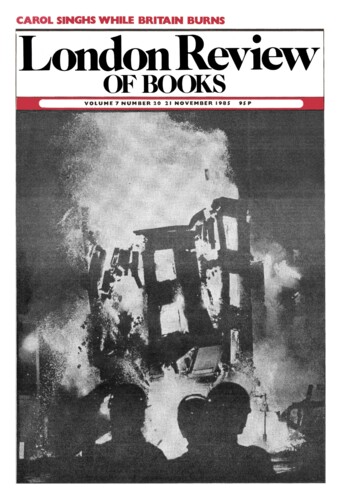

The urban riots which punctuated the conference season may be part of the explanation for this. The absence of the Government during the long recess sometimes makes the voters’ hearts grow fonder. Boredom and disillusion have to be set against a continuing upward trend in real incomes for the majority of the population which remains in employment. But the election study suggests that if any party can lay claim to being the natural party of government it is still the Conservative Party. In the spread of its electoral support it is virtually a classless party – at its conference this year it actually looked like a classless party – and ideologically it is most in tune with the shift in the electorate away from state intervention and towards privatisation. If all the parties were to poll their full natural class support (which even in 1983 the Tories failed to do), the result of a general election in 1987 might be: Conservatives 45 per cent, Labour 35 per cent (up on 1983 but still down on 1979), and the Alliance 20 per cent. That is not a prediction of the result of the race; it is a calculation of the handicap.

The Conservatives may not win the next election, they may not even finish as the largest party. Margaret Thatcher will have been around for a long while by then, and people may be thinking that it is time for a change. Even if tax cuts are fructifying in the pockets of the employed, people may also be beginning to wonder where the money is going to be coming from when the oil runs out. Some of the consequences of the decline as charted by the Select Committee of the House of Lords, in a devastating report backed by two thick volumes of even more devastating evidence, may have become more visible by then. For all that, it is difficult to envisage an alternative majority while the Left remains divided. If three-party politics are here to stay, it is in the sense, not of an even three-cornered contest, but rather that neither Labour in its class and ideological decline nor the Alliance with its still embryonic constituency looks capable, at least at the next general election, of resolving the contest on the left. Conservative government by default is another of the morbid consequences of the post-socialist age struggling to be born.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.