Awoman waits in a bare room for a meeting with her lover, who has been detained as an anti-colonial agitator. He is escorted from the cells by a Portuguese plain-clothes officer. This is Angola, sometime in the 1960s. The couple embrace; he asks for news of their children. Waiting outside, the security man overhears the woman promise to bring the prisoner a ‘full suit’ on her next visit. He reports this to his superior, sealing the prisoner’s fate. Monangambeee (1969) was Sarah Maldoror’s first film, based on a short story by the Angolan novelist José Luandino Vieira. It turns on a misunderstanding about what has been said. The security guard takes the words ‘full suit’ – fato completo in Vieira’s Portuguese – to suggest that the detainee has hopes of appearing, respectably dressed, before a tribunal to plead his case: he is separated from the other prisoners, beaten and starved. At the point of death, he receives the gift he was promised – a pot of fish, bean and plantain stew, known by Angolans as a fato completo.

At eighteen minutes, Monangambeee is a miniature of the anti-colonial struggle in Portugal’s African colonies. The misunderstanding of the colloquialism, which represents the coloniser’s ignorance of the lives and idioms of the colonised, will take the struggle to a claustrophobic pitch in the detention centre. The script, which includes a short monologue about hunger delivered by the prisoner to a lizard in his cell, is pared back. Two scenes are carefully choreographed: in the opening moments of the film the reunited couple have the finesse and economy of dancers; near the end, the pain of the prisoner under torture is performed as a mime without a torturer and scored – like the rest of the film – by the Art Ensemble of Chicago.

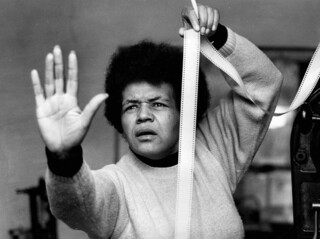

Much of Maldoror’s approach over her long career is set out in Monangambeee. ‘I am black,’ she told Marguerite Duras in 1958, ‘I need to think of myself as black.’ She was also a committed anti-colonialist: monangambeee is an elongation of the Kimbundu word for ‘contract labourer’; it was one of the rallying cries of the Angolan liberation movement. Maldoror honoured independence struggles in Africa and other parts of the world throughout her life. But she wouldn’t set aside her values as a filmmaker in the name of a cause: ways of seeing had to be learned and owned, or there was no seeing at all. Working on The Battle of Algiers (1966) with Gillo Pontecorvo, she was assigned to the casbah in Algiers, to win the trust of Algerian women, many of whom agreed to take part in the film. Yet her sense of how to handle a harrowing scene in detention is quite unlike Pontecorvo’s neo-realism. ‘I have no time to make didactic political films,’ she said after the release of Sambizanga (1972), her full-length film set during the anti-colonial struggle in Angola.

She went on to make dozens of films: dramas, documentaries and an impressive array of shorts for French TV. Some were notes and drafts in cinematic form, no longer than ten minutes. The list of poets, intellectuals and artists whose work she presented or adapted for the screen includes Aimé Césaire and Léon-Gontran Damas, founders of the négritude movement, and their fellow Caribbean poet René Depestre; the Cuban artist Wifredo Lam; the French poet Louis Aragon; the French photographer Robert Doisneau; the Russian-Mexican painter Vlady Rusakov and his father, Victor Serge, hero of the anti-Stalinist left. Several of her works are lost, including The Commune, Louise Michel and Us, a film she worked on in the early 1970s and ‘Guns for Banta’, a feature she shot in 1970 in Guinea-Bissau during the liberation war against the Portuguese.

Maldoror moved on from her successes as briskly as she did from projects that never came good. She was generous with her own material. In Chris Marker’s peripatetic essay Sans Soleil (1983), the documentary footage of liberation fighters in Guinea-Bissau was shot by Maldoror; she gave it to Marker with no strings attached. She was collegiate to a fault as long as your project made sense to her. Her own consuming interest during the 1960s and 1970s was the second wave of African liberation, above all in Guinea-Bissau and Angola.

Because Maldoror raised most of her funding in Europe, Paris became her base. She was fascinated by its intellectual tribes and also by its mixité. She was an aficionada of poetry and jazz: she heard both as calls to liberation, involving risk, experiment and the courage to fail. In the early 1970s she set up camp in Saint-Denis at the margins of the capital and the banlieues, at ease in a département that had been run by the Communist Party since Liberation in 1944. She had plans to document the neighbourhood, with its mainly working-class residents – many of African descent – but the only piece she completed is the lost The Commune, Louise Michel and Us.

A short film on the basilica of Saint-Denis, which she could see at the end of the street whenever she left her apartment, has survived. The centrepiece of Abbaye Royale de Saint-Denis (c.1977) is a study of the royal necropolis in the cathedral, where the remains of kings and queens are entombed beneath effigies and elaborate pavilions. With its placid close-ups and simple pans, her exploration of mortuary grandeur resembles a set of drawings in a sketchbook. They speak to her powers of concentration rather than her political position, even though we know that she was a republican and a revolutionary, and that many of the tombs were desecrated in 1793. The camera lingers on a 13th-century bas relief of demons taunting the soul of King Dagobert, a drama in stone whose protagonist she dignifies, like the prisoner under duress in Monangambeee. In the voiceover, we hear the words of the Abbé Suger, the first abbot of Saint-Denis, and funeral orations by Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet; the score consists of plainsong and passages from Couperin. Maldoror’s ears were as sharp as her eyes: she liked her work to look good and chose her music carefully. None of this struck her as a bourgeois distraction from politics, even in films that deal directly with life and death struggles in colonial Africa.

Marguerite Sarah Ducados was born in 1929 in the Gers, in south-west France, where her mother worked as a maid. Her father was a black Frenchman from Guadeloupe, who died when she was young. She was one of four children in a single-parent family and spent periods in an orphanage. By the 1950s she was in Paris, where she found work as a PE instructor and enrolled at the school of dramatic arts in the rue Blanche. She was one of a group of students, all of them black, who put together a small theatre company. Les Griots described themselves as an African performing arts company. They staged readings from Césaire and had their first success with a production of Huis Clos. Skin colour was no obstacle to casting Sartre’s piece or their subsequent productions (among them Pushkin’s The Stone Guest and Synge’s In the Shadow of the Glen): to identify as black was a badge of defiance, both culturally and politically, as the call for African independence reached Paris and France’s undeclared war in Algeria intensified.

Ducados took her pseudonym from Les Chants de Maldoror, a transgressive prose piece in six cantos composed in the 1860s by the Comte de Lautréamont and ‘rediscovered’ by the Surrealists between the wars. ‘Lautréamont’, too, was a pseudonym, adopted by the French-Uruguayan Isidore Ducasse (1846-70): it was an uncomplicated step from Ducados via Ducasse to Maldoror, with a nudge from the writings of Césaire, for whom Lautréamont was a revolutionary inspiration. Maldoror had a growing number of influential admirers in Paris. She met the publisher François Maspero at his bookshop La Joie de lire when she asked if she could put up a poster for a show; they forged a close friendship.

The exiled Angolan anti-colonial activist and poet Mário Pinto de Andrade became her partner for life. Like many intellectuals from Portugal’s colonies who went to study in Lisbon, Andrade had fallen foul of the regime’s security forces in the early 1950s (we glimpse them at work in Monangambeee). In Paris he was offered an editorial post at Présence Africaine, a journal whose star was in the ascendant. The first issue had appeared in 1947; its energetic young editor, Alioune Diop (another of Maldoror’s contacts), started a book-publishing imprint shortly afterwards. Andrade and Diop drew a community of black intellectuals, including African Americans like Langston Hughes and Richard Wright, to the offices of Présence Africaine. Andrade was working with Césaire on a new edition of his long poem Cahier d’un retour au pays natal and compiling an anthology of African poetry. In 1956 Diop organised the first Congress of Black Writers and Artists at the Sorbonne, where Maldoror is said to have met Andrade and begun her lifelong alliance with Césaire.

Les Nègres, Jean Genet’s subversive masque – or ‘clownerie’, as he called it – was published in 1958. In it, a racialised murder is re-enacted by ‘black’ culprits as a performance within a performance, which pits a panel of decadent white dignitaries (played by black actors) against the accused (also played by black actors). Intrigued by the piece, Maldoror convinced Genet to let Les Griots stage it and enlisted Roger Blin to direct. The production was sure to draw attention: Genet was already notorious for his lyrical novels about crime, prisons and homosexual love; Blin was a familiar face on French cinema screens and a theatre director with the first production of En attendant Godot (1953) to his credit. That Genet should give the first performance rights for the play to an outspoken young black woman was both titillating and scandalous. Maldoror’s spiky interview with Marguerite Duras in France Observateur was published shortly after the news got about.

Duras: Why do you want to play Les Nègres in front of white people and not in front of blacks?

Maldoror: Because we don’t know one another … because we are not on an equal footing with whites … we have only one way to overcome our past, as determined by you. And that is to play on this past: to make fun of the blacks as they’re seen by whites.

Duras: For your amusement and that of whites?

Maldoror: No. For our amusement and your education.

Duras: Our education matters to you?

Maldoror: Absolutely … We will never be free for as long as you see us the way you see us. For us to become free blacks, we have to rid you of the idea you have of us. We need you … to forget what you were taught at school about blacks. Because here you are, interviewing me and thinking you know about the problem for blacks, but you don’t know!

The play opened at the Théâtre de Lutèce in October 1959. Le Monde called it one of the most exciting pieces of the season. But Maldoror, who had done so much to bring it about (and probably rehearsed for the role of the queen), was no longer involved. She had made common cause with Andrade: Africa was the new theatre of struggle and she threw herself into it. A few years later, Les Griots was reinvented with the help of Med Hondo, the Mauritanian-French film director who sealed his cinematic reputation with Soleil Ô (1967). A little younger than Maldoror, trained like her in drama school and raised on Chekhov and Molière, he was her obvious successor.

By the end of 1959 Andrade and Maldoror were in Guinea-Conakry, at the invitation of the new head of state, Sekou Touré, a radical who had led the country to full independence from France in 1958 and opened up Conakry as a talking shop for African liberation movements. Andrade was one of the founders of the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola. In 1960, Agostinho Neto, a senior MPLA colleague – and another poet – was jailed by the Portuguese. Andrade was appointed head of the MPLA and given an office in Conakry.

Maldoror had long been intrigued by the messy entanglement between the Surrealists and the French Communist Party: she was a keen reader of Surrealist verse – and later a friend of Louis Aragon – as well as a staunch supporter of the party (and perhaps a member). In Conakry she was awarded a bursary to study at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography in Moscow, where she met Ousmane Sembène, a central figure in modernist African cinema. Her first child, Annouchka, was born in Moscow in 1962.

Mother and daughter left the Soviet Union the following year. ‘I’m not sure where we went,’ Annouchka told me when we met recently in Paris. Perhaps they returned to Guinea-Conakry. If so, it would have been a brief stay, before a move to Morocco, where Maldoror spent a year or more and where Annouchka’s sister, Henda, was born. For much of this time Andrade was with the family. Morocco, like Guinea-Conakry, was a haven for anti-colonial activists, although the young Hassan II would soon distance Morocco from African liberation movements. In March 1962, Andrade (and Nelson Mandela) received military training from a detachment of Algerian Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) fighters posted across the border on Moroccan soil. A few months after Mandela’s visit, the French withdrew from Algeria. In 1964, as Andrade plied the African liberation networks, Maldoror and the children joined him in Algiers, the new anti-imperialist metropole of the Third World. Two years earlier Neto had escaped from prison in Lisbon and taken over the leadership of the MPLA; Andrade had bowed out gracefully. Now he was taking stock of his situation. Maldoror was scouting for commissions.

Algiers was humming with revolutionary resolve. Maldoror arrived as cinema was about to lift off there. Elles, a short documentary by Ahmed Lallem released in 1966, took its cue from Chronique d’un été, inviting Algerian girls, most of them teenagers, to speak to camera about their hopes for the future as women in a socially conservative country. Lallem brought Maldoror on board as assistant director. Elles and The Battle of Algiers marked the beginning of her career in film (her payslips from the Pontecorvo shoot became family souvenirs). In both cases she was an intermediary between male directors and the women they wanted to film. In 1968 she began working on Monangambeee.

Pan-Africanism had faltered as a political programme, but it was about to be reinvented as a spectacular cultural project, hosted by the regime in Algeria. The legendary Pan-African Festival in 1969 – recorded in the documentary by William Klein, with Maldoror working in the second camera crew – drew hundreds of artists and performers to the city, among them Nina Simone, Miriam Makeba, Manu Dibango and the jazz saxophonist Archie Shepp.* Shepp and Maldoror became friends, and he appeared in her last short film in 2003. The African Cinema Week was one of the festival’s attractions (Sembène was in attendance) and movies seemed to be on everyone’s minds, including Algeria’s ruling party. Pontecorvo had pioneered a path for Costa-Gavras, who went to Algeria to shoot many of the scenes in Z (1969), his thriller about the turmoil in Greece, where a military junta had recently seized power. The FLN agreed a co-production deal. It had also put up money for Klein’s documentary and for Monangambeee, which was approved for release a few months after the festival. ‘Having screened the film,’ the official report went, ‘the Department of Orientation and Information can find no impediment, on political grounds, to its distribution.’ This was high praise from a regime that was already on the alert for ideological error.

Maldoror and Andrade savoured the postwar mood in Algiers and entertained many visitors and expat revolutionaries at their home in Saint-Eugène, a few miles along the coast from the city. Annouchka remembers a flurry of delegates from Cuba, among them Che Guevara. Amílcar Cabral, the leader of the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC), was a regular guest and Andrade’s closest friend – they had met in Lisbon in 1948. All African liberation movements were entitled to military training in Algeria, but their members generally turned up unarmed in Saint-Eugène, although Annouchka recalls that more than once her mother had to remind Eldridge Cleaver to leave his guns by the door.

Weapons – or rather, armed struggle – would be the subject of Maldoror’s first feature-length film. The FLN’s military wing, by now firmly in charge of Algeria, was willing to fund her project, which was shot in Guinea-Bissau, where anti-colonial guerrillas were making headway against the Portuguese. With Cabral’s assistance, Maldoror was received by the fighters in the bush and found a way to dramatise her documentary footage, devising characters based on militants and villagers she met. She returned to Algiers in 1970 or early 1971 with enough footage for a feature. Its title, ‘Guns for Banta’, referred to a village in guerrilla-held territory.

‘I was thrown out of Algeria,’ Maldoror said in an interview on Radio France Internationale in 2019, the year before she died. ‘But I wasn’t the only one. And so what?’ Her Algerian funders weren’t happy with her cut. Awa, the central character, was a woman; this was inappropriate, the FLN felt, even though many Algerian women had risked their lives in the fight against France. And she had opted for a jazz soundtrack, which went against the grain of the FLN’s nationalist renaissance. She was furious with the army staffer who gave her the news. It was her film, she told him, not his; as far as she was concerned, he was a fuck-all subaltern, a ‘capitaine de merde’. He was a senior officer, he corrected her, and would have killed her if she hadn’t been a guest of the FLN. She was given two days to leave the country.

Cabral was in Algiers when the row erupted and, according to Annouchka, he and Andrade escorted Maldoror to the airport, fearful for her safety; at the terminal in Paris, where she might still be in danger, she was met by members of the PAIGC. Before long, with help from Marker and Madeleine Alleins – the lawyer of the deposed Algerian president Ahmed Ben Bella – she set up home in Saint-Denis where the children joined her. She was soon back at work on the now missing film about Louise Michel, feminist, anarchist, educationalist and ‘la pétroleuse’ of the Paris Commune, which was commissioned by the city of Saint-Denis, and shot and edited in 1971.

At the insistence of the Portuguese government, Andrade was on an Interpol list of subversives, but he had several passports issued by newly independent African states in several different names, and managed to visit the family from time to time, flying to Brussels and travelling by car to Paris. The independence of the Portuguese colonies had become the focus of Maldoror’s life as well as his. Andrade was now president of a co-ordinating body for the four anti-Portuguese movements in Africa. But national priorities were already more pressing; he was close to Cabral and impressed by the success of the movement in Guinea-Bissau, but deeply preoccupied by Angola, where the MPLA was under pressure, not least from internal dissent and the existence of rival movements.

Maldoror’s next film was a drama about Angola, set not in the turmoil of the present but in 1960 as the anti-colonial movement prepared to take up arms. Sambizanga is in many ways the precocious sibling of Monangambeee, which was shot in 16 mm black and white film and based on a short story. Sambizanga was shot on 35 mm stock, in colour – running time 98 minutes – and based on a novella, again by Luandino Vieira. In both films, the arrest of an activist sets off a series of events that ends with a death in detention. But in Sambizanga the partner of the detainee (played by Elisa Andrade in both films) is the central character: Mária isn’t a fighter – this isn’t ‘Guns for Banta’ – so much as a lowly Penelope who abandons her loom and sets out in search of her missing nobody, Domingos Xavier, a tractor driver in a stone quarry and a member of an anti-colonialist cell. The police have seized Domingos in the quarry workers’ compound near Dondo, an inland provincial city, but when Mária learns that he has been transferred to Luanda, she sets off with their infant on her back. Her final destination is the sprawling musseque of Sambizanga on the edge of the city. She goes from one police station to another for news and finally locates Domingos in a centre for political prisoners, but not in time to see him alive.

The spine of the film is a road movie. Mária’s journey to Luanda is among the most memorable sequences in Maldoror’s work. Benign, semi-mountainous landscapes of woodland and misted valleys, which Mária observes from the window of a bus, evoke a prelapsarian past, or perhaps a future beyond violence, in any case a world without colonial rule. She trudges for what might be hours on tracks surrounded by lush vegetation. Yet for much of the time our attention is on the inclination of her head, her gaze shifting from the window or the edge of the road to her own thoughts, as the reaction shot becomes the main event. Conjuring an inner world that takes the measure of real contradictions for millions of Angolans – between their disempowerment and their obstinate wish for something better – is a tall order. Success or failure hangs on the inflection of Mária’s eyes.

Maldoror liked to set herself problems. How do you film an interrogation? What attitude on the part of your actors most accurately depicts grief in a world where people are called on to die for a cause? Is it possible to shoot a drama about politics and avoid laying it on thick? In a short scene set in the provinces we’re introduced to Mussunda, a tailor who’s part of the anti-colonial movement, as he chalks up a length of fabric (an echo of the ‘fato completo’ in Monangambeee). He is lecturing his apprentices about the struggle: it’s not a conflict between blacks, whites and mulattos, he argues, so much as a class war between rich and poor. When a junior tailor protests that the rich provide work for the poor, Mussunda disagrees. Maldoror’s challenge, we sense, is to ensure that the monologue that follows – in which Mussunda’s position is close to her own – doesn’t seem glib or doctrinaire. In a view along the length of the shop we see the cutting tables and sewing machines; at the far end, net curtains billow at a window; to the right a bright plastic fly-curtain shifts in the same breeze. We feel the circulation of free discourse, like the air in the room, while the whirr of the sewing machines grounds the argument in the domain of work – an argument that could land these skilled labourers in detention.

How to handle Domingos’s death was another challenge, solved by cutting from the interrogation to a pair of guards dumping his near lifeless body in an overcrowded cell. The prisoners dab tentatively at his face as he dies, adjust his arms by his side and sing a low, ragged lament. This typically understated approach gives Maldoror space to let Mária/Andrade off the leash in extravagant performances of rage and despair, before the film returns to its matter-of-fact tone. Maldoror’s only concession to grandiloquence is to have Domingos’s death announced at an open-air dance attended by militants. The old Domingos is dead, a senior figure in the movement tells the guests, but his ‘real life’ – as in the title of Luandino Vieira’s novel – has just begun. He is now immortal, a martyr for the cause; no tears should be shed; the band must play on. The country is on the verge of an uprising that will mark the start of its armed struggle against the Portuguese.

Maldoror filmed Sambizanga in independent, francophone Congo-Brazzaville: shooting in Angola in the early 1970s was out of the question. The landscapes are plausibly Angolan; the colonial lingua franca, which accounts for most of the dialogue, is Portuguese, not French. At the time, many independence activists from Portugal’s colonies were in Brazzaville, including Elisa Andrade and Domingos de Oliveira, an MPLA member, who plays Domingos; small parts were also taken by Angolans, none with previous acting experience. Sambizanga picked up a prize at the Carthage Film Festival in 1972, and in 1974, following the overthrow of the Estado Novo regime in Lisbon, it was watched by sizeable audiences in Portugal.

All the same, it wasn’t to everyone’s taste. Why wasn’t the anti-colonialist message hammered home? Where were the helicopters raking the forest with bullets and the intrepid liberation fighters returning fire? Why was the film so technically accomplished: wasn’t this the wrong aesthetic for a rousing tribute to the struggle? In the tenor of these criticisms Maldoror may have heard an echo of her ‘capitaine de merde’. She responded in an interview for the journal Women and Film in 1974. Her film was set in 1960, she explained, and the helicopters only arrived later, after the Portuguese became alarmed by the rise of a new ‘consciousness’ among Angolans. And besides, she had no interest in ‘political rhetoric’. On the question of quality: ‘Technology belongs to everyone. “A talented black”: you can relegate that concept to my French past.’ She went further: ‘The colour of a person’s skin is of no interest to me … I’m not a subscriber to the concept of the Third World. I make films so that people – no matter what race or colour – can understand them.’ This was elementary Marxist internationalism in its 1970s iteration, even if her position was more nuanced than she was willing to admit. When the same criticisms resurfaced in the 1990s, there was an additional reproach: her actors were too good-looking. ‘The main actors, the man and the woman are beautiful,’ she agreed. ‘And so? There are beautiful black people [des beaux nègres]. What do you want to hear? If I get to choose between beautiful and less beautiful actors, I choose the beautiful ones.’

Sambizanga took Maldoror on tour, mapping out new ideas as she attended screenings. Andrade remained an itinerant diplomat for African liberation. She often called on him for help. She had long been a voracious reader, pillaging copies of new titles from Maspero, Présence Africaine and Seuil as they came off the presses, but she was a reluctant writer and drew the line at drafting scripts. A letter to Andrade, sent while Sambizanga was in pre-production, explains that she can’t get started unless he lends a hand with the writing. His name duly appears in the credits.

The couple were in intermittent contact over the next few years. In 1973 Cabral was murdered while visiting Guinea-Conakry. Maldoror made an unauthorised trip to Guinea-Bissau, crossing on foot from Senegal to join the PAIGC maquisards and shoot material for a documentary which was never finished. She and her cinematographer were hosted by PAIGC fighters, including Luís Cabral, who had replaced his half-brother as leader of the party: this was the footage that came to light many years later in Marker’s Sans Soleil. In April 1974, the coup in Lisbon did away with the Portuguese regimes in Africa: Guinea-Bissau was granted formal independence six months later. For Angola, it came the following year. Andrade – who didn’t see eye to eye with Neto – had already distanced himself from the MPLA. He was invited to Guinea-Bissau by the PAIGC government and ran its ministry of culture for several years. At Maldoror’s suggestion, he invited Marker to train the country’s novice filmmakers.

Sambizanga had rewarded Maldoror with work. A number of films followed, among them a documentary with Césaire in Martinique; Un Dessert pour Constance, a sharp comedy about two Senegalese street cleaners in Paris; and a dozen short items, mostly for a French TV magazine slot. This prodigious output enabled her to support Andrade, who asked no favours from the PAIGC, and to raise their children, despite periodic crises. ‘I’m unemployed,’ she wrote to a government minister in Guinea-Bissau in 1982, urging him to track down the master of ‘Guns for Banta’ in Algiers. ‘I’ve got problems.’ But within months she had won a commission from French TV for a drama based on a story by Victor Serge.

L’Hôpital de Leningrad (1982) is one of Maldoror’s great achievements. Like Serge’s piece, her film is set in a rundown psychiatric hospital, whose deputy director welcomes Victor Lvovich – that’s to say Serge, played by Rüdiger Vogler – and shows him round. Serge’s wife is suffering from a mental disorder: he is checking out the hospital, which doubles as a facility for counter-revolutionaries and other offenders. We know from the date on a manuscript in one scene that we’re in the early 1930s. We can also guess from the buildings, the barred windows, the new arrivals being bundled out of a truck in the yard by soldiers, that the overarching mood in Stalinist Russia is fear. Serge’s piece asks whether there is any escape, and if so, at what price? A new confinement in a world of delusion possibly? And a return to the prison system that the fugitive has ceased to be afraid of? Maldoror sticks closely to Serge’s questions.

Touring the hospital, he encounters a young woman who served two stints in Siberia, ran away and was recaptured, and a new detainee, who has just been arrested with her fellow workers in a shoe factory: she asks Serge to remember her name and address. In a well-appointed cell, the doctor introduces him to Nestor Petrovich Yuriev, a ‘lover of literature’ (played by Blin). They are soon talking frankly. ‘Are you afraid?’ Nestor asks. ‘Yes, sometimes, like everybody else.’ ‘If you’re afraid, forgive me, you’re an invalid who cultivates his illness … Fear is an infectious neurosis … I used to have it, but I’m better.’ Nestor, it turns out, woke up one day to discover he was cured. He dashed off an ‘appeal to the people’ on forty identical handwritten fliers and posted them around Leningrad, adding his address at the bottom. ‘Citizens, why are you trembling? Why are the members of our great Communist Party trembling? Why does the government uncover plots that don’t exist? … Look loyally at each other without fear and this nightmare will crumble.’ The following morning he was waiting with a packed suitcase for OGPU agents to take him away.

Under duress, he speaks frankly about the ‘infectious neurosis’ to his interrogators and adds in quiet, messianic tones that they’ll never forget what he’s told them. Some are already at risk of recognising their own symptoms. Serge’s narrative ends at this point, but Maldoror adds a scene in which he returns home to his distraught wife, Liuba Rusakova (played by Anne Wiazemsky). Convinced that he’s been followed by the secret police she confesses her ‘fear’: they’ll both have to live with the possibility that she’ll go mad. Serge reprimands her: ‘Never use that word again.’ You think at first he means ‘mad’. He goes to his desk. Liuba picks up a book and reads aloud: ‘I know the force of words/the alarm they sound … so often unpublished, unprinted’ – lines by Mayakovsky that turned up after his suicide. Why won’t Serge acknowledge that his writing is a suicidal mission? Without a party card, he’s unpublishable, unprintable, fatally exposed as an oppositionist. Liuba throws the volume of poems at him. In the closing scene, as he leaves the apartment building, agents are waiting for him, just as they were for Nestor. Maldoror’s women know more than her men. Not that they always have the last word, as Liuba does, but we should imagine Maldoror’s bereaved characters as active contributors to the cause, protracting it beyond the point of personal crisis. This is easier when we think of her characters in Monangambeee and Sambizanga than for Liuba, though she outlived Serge by nearly forty years. ‘I am only interested in women who struggle,’ Maldoror said in her interview for Women and Film.

At the end of the 1980s, Maldoror took advantage of a visit to Atlanta to head for Mexico City and show her film about Serge to his son, Vladimir Rusakov. She had heard that Vlady, who had arrived in Mexico with his father in 1941, was a painter. A chamber in the oratory of San Felipe Neri had been converted into a library and he had been commissioned to paint a set of murals for it. Maldoror found this vast project irresistible. Vlady, Peintre (1989) is both an interview with Rusakov, then in his late sixties, and a visual record of his epic set of allegories, Las Revoluciones y los elementos. Her camera sweeps along the walls as he talks her through his idiosyncratic vista of revolutions, including Christianity, the English, American and French revolutions, the Bolshevik revolution, the revolutions in Latin America, even the psychoanalytic revolution.

The paintings teem with rising demons, plummeting angels and lost souls. Cromwell’s head sprouts from the tail of a grotesque serpent; English despotism, in royalist mode, is portrayed by two Englishmen – Ronnie and Reggie Kray – imprisoned in the Tower of London, as they were for a few days in the 1950s. The ascending demon of Bolshevism is depicted as a fiery archangel with winged feet, wielding axes that seem to grow from its hands. Bolshevism, Rusakov explains in voiceover, was part of ‘our barbarity’: ‘The struggle for justice is as cruel as justice itself.’ Fidel Castro appears astride an enormous dinosaur. Votive portraits peep through the fury: Fidel’s young French protégé, Régis Debray; Oscar Romero, archbishop of San Salvador, murdered by a right-wing death squad in 1980. A panel depicts the death of Trotsky in 1940, his desk overturned in his study: Rusakov tells Maldoror he remembers his father crying after visiting Trotsky’s house in Coyoacán. One tableau shows Serge’s body, as his son glimpsed it, at the back of a police station in Mexico. The holes in the soles of his shoes are the stigmata of the exemplary, defeated revolutionary.

Maldoror’s views by now were close to Serge’s. She might not have agreed with Rusakov that revolutionary politics seeded its own failure – a realist in practice, she remained an optimist by temperament – but Revoluciones y los elementos, which seemed to have spooled from Rusakov’s imagination and become a sequence of majestic stills projected onto the library walls, was fearless and not entirely without hope. Cinema for Maldoror was as much a sister art to painting as painting was to poetry. On the eve of a production she sometimes gathered her cinematographer and crew, and sat them in front of a painting, to give them a sense of the way she would like the film to look.

When Andrade died in 1990, Maldoror was in her late sixties and went on to finish another eight films. In 1994 she made a documentary about Damas, a poet and co-founder of the négritude movement, in his native French Guyana. She decided to shoot in black and white and the French TV commissioners refused to broadcast it. It was the last of her serious run-ins with the networks. Scala Milan AC (2003) is a short comedy about a group of schoolchildren from a working-class area of Paris who win a trip to Milan. After the loss of Andrade, Maldoror was on her own with the screenplay. Like Monangambeee, Scala Milan AC is based on a misunderstanding. Maldoror’s group of teenagers in the 20th arrondissement enter a competition for the best description of their neighbourhood. In Père Lachaise cemetery they come across Archie Shepp, riffing sweetly among the tombstones. When he lifts his mouth from his instrument to introduce himself – ‘I’m Archie Shepp’ – it’s as though a grand mystery had been cleared up: a Wizard of Oz moment without the bathos. Shepp gives some sound advice to the children, who win the competition and set out for Italy in high hopes of a visit to the San Siro stadium, even a glimpse of AC Milan in action, only to discover that they’re headed for La Scala. In the event, they’re not disappointed. For Maldoror ‘high’ culture was a free-for-all in theory if not in fact. The Fifa anthem ‘Nessun dorma’ had opened up this possibility. The credits roll with special thanks to Agnès Varda, Maldoror’s sponsor on this occasion.

In 2009, Maldoror finished a documentary tribute to Césaire, who had died the previous year. There were no more films before her own death in 2020, after being diagnosed with Covid. Her career ends with an acknowledgment of négritude and an homage to a founding member of the movement. But, like Césaire’s, her view of politics took her well beyond an essentialist celebration of black identity. Césaire had already come to a revisionist view of négritude as an occasion for Africa and the diaspora to live their own ‘history within history’ in the broader sense proposed by Marxism. Maldoror would have concurred. Many ‘races’, after all, were caught up in the liberation struggles of her day, from Indochina to Latin America. ‘From Négritude to Guerrilla War’, a typescript treatment for a series that she never made, begins with a schematic explanation of négritude. Some, she writes, regard it as an Africanist ‘humanism for the 20th century’, others as a ‘dangerous mystification’. (Her schema hints at a closing film about Frantz Fanon, who took the latter view.) One of the ‘dangers’, it seems, lay in dissociating African liberation from other causes. A few years earlier at the Carthage Film Festival, she had fought tooth and nail with her fellow jury members, insisting that a Palestinian film should be rewarded on principle, irrespective of its merits.

Yet Maldoror was reluctant to shrug off négritude as the racialised framework in which her internationalist convictions had developed. Sartre had argued at the end of the 1940s that this was the way the movement should play out, but for Maldoror, as for Césaire, négritude was not an open-and-shut case. The literature remained eminently readable; its exponents had opened a key cultural front in the anti-colonial struggle and the dust had yet to settle. Perhaps, too, she had seen the tactical necessity of championing an essentialist-lite version of blackness. If the imperial powers had invoked a Eurocentric universalism as a cover for their own ambitions in Africa, then négritude – and pan-Africanism – were entitled to even up the score.

It may be too simple to say that Maldoror’s argument about race with Duras in 1959 and her remarks about the irrelevance of skin colour fifteen years later represent a shift in her beliefs. Surely it was possible to hold the two sets of thoughts in animated tension – to regard race as paramount at one moment and lose patience with it the next. Often it depended on the conversation she was having and the person in front of her. The same holds for her repudiation of Third Worldism. So many of her films dealt with Africa and the Caribbean that she was, for much of her life, a working tiers-mondiste, or at least a fellow-traveller. But there was no suggestion in her own mind that this should keep her away from ‘white’ subject matter (cathedrals, European poets and painters, the crimes of Stalinism) any more than her feminism would have disqualified her from making films about men.

In Le Masque des mots (1987), another of her films about Césaire, he remarks: ‘I appear to myself, when I’m writing a poem, as a person wearing a mask.’ Maldoror understood the value of masks from her days with Les Griots. Far from being banal deceptions, they are invitations to consider what is real and what isn’t, as Genet had done in Les Nègres. Often masks that fit disclose more than they conceal. Masks that slip, as they do with her novice actors in Sambizanga, allow us a glimpse of someone (or something) else, in this case colonial subjects, barely disguised as versions of themselves, enacting a constructive dismissal of colonialism. Masks, as she knew, have the power to reorder the realm of appearance – in carnival, ritual and above all in the political cinema at which she excelled. The idea that seeing is believing didn’t work for her. Maldoror was happier to start out with a set of beliefs and put them to the test.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.